When you think of a rivalry that has stood the test of time, few can compare to that of Aristotle and Plato. Old Greek thinkers really left their mark, diving deep into what makes us tick, how we should live together, and the big questions of life. But what sets them apart? But why do we still find ourselves hooked on their argument, even now? From student-teacher dynamics to fundamentally opposing views on reality’s nature, this exploration isn’t just about two historical figures; it’s about understanding the very fabric of human thought.

Table of Contents:

- The Philosophical Rivalry Between Aristotle and Plato

- Aristotle’s Conception of Substance and Form

- Actuality and Potentiality in Aristotle’s Metaphysics

- The Influence of Aristotle’s Philosophy

- Understanding the Human Condition Through Aristotle and Plato

- Conclusion

The Philosophical Rivalry Between Aristotle and Plato

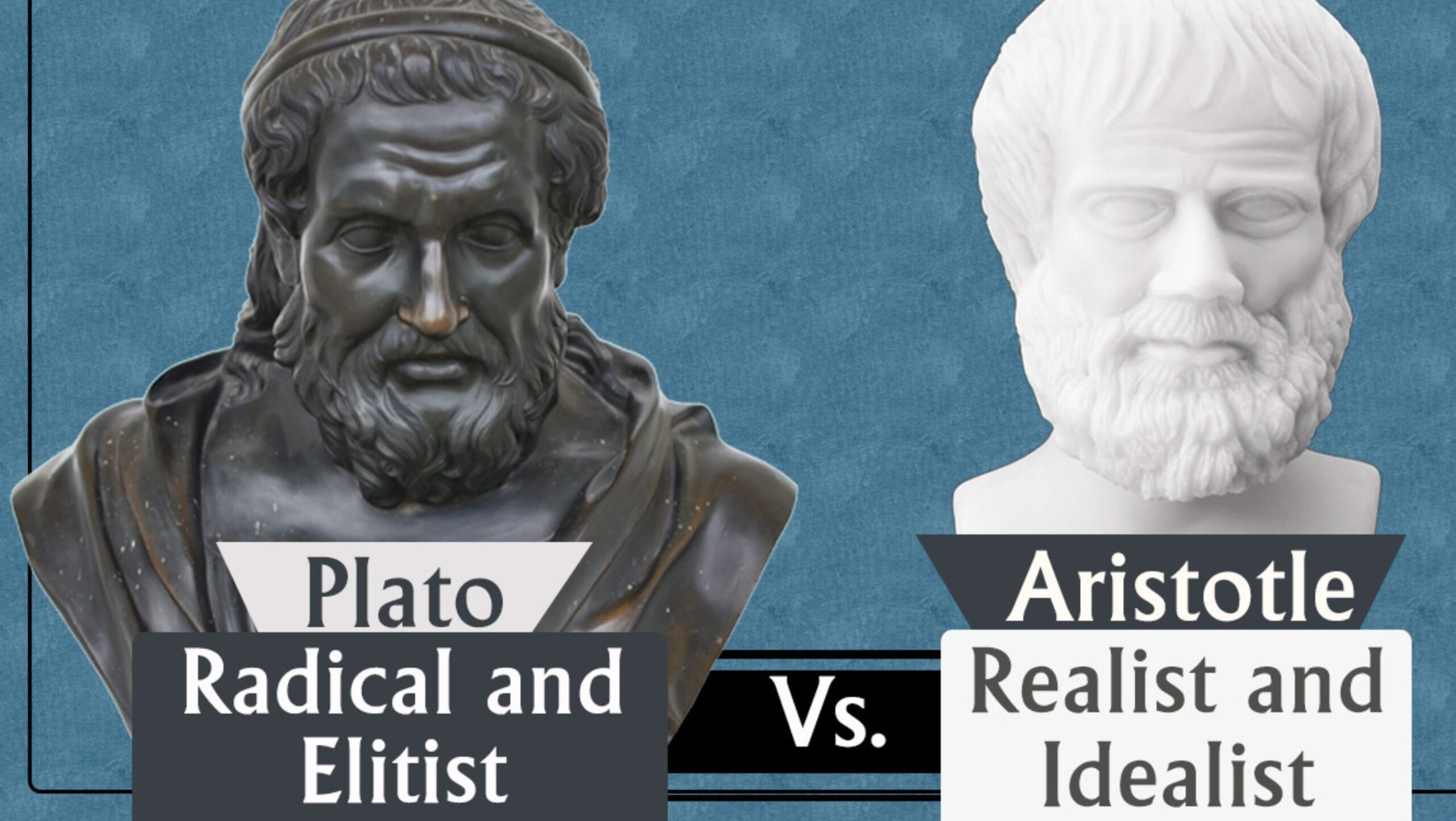

Aristotle and Plato – two of the most influential ancient Greek philosophers who shaped Western thought. Yet despite being Plato’s student, Aristotle ended up rejecting many of his mentor’s core ideas, sparking a philosophical rivalry that would reverberate through the ages.

So what led these two great thinkers, once teacher and pupil, to become intellectual rivals? It boils down to fundamentally different ways of understanding the world.

Aristotle’s Critique of Plato’s Theory of Forms: Aristotle and Plato

Aristotle took issue with Plato’s famous Theory of Forms, which held that the reality we perceive is just a shadow of the true reality of eternal, perfect Forms. Plato believed that these Forms exist independently in their own realm and that we can only access them through reason, not our senses.

But Aristotle wasn’t buying it. He thought Plato’s theory was too abstract and divorced from the reality we actually experience. For Aristotle, the forms of things don’t exist in some separate realm – they’re intrinsically tied to the physical objects themselves.

As The Collector explains, “Aristotle doesn’t just disagree about how we come to know what we know. He also disagrees with Plato about how things are.”

Aristotle argued that we can only understand something by studying both its form (its essence) and its matter (what it’s physically made of) together. A chair’s “chairness” can’t be separated from the particular wood, nails, and craftsmanship that make up an actual, physical chair.

The Divergence in Their Philosophical Approaches

This disagreement about forms was just one part of a broader split between Plato’s rationalism and Aristotle’s empiricism. Plato held that we gain knowledge through rational thought and reflection, not sensory experience. But Aristotle believed we can and should use our senses and experiences to understand the world.

As philosopher Arthur Herman writes, “For Aristotle, we can use our experiences to develop an understanding both of the structure of things, and of the material by which they are composed.”

These different starting points led Plato and Aristotle to very different conclusions about knowledge, reality, and even politics. While Plato distrusted democracy and material pleasures, seeing them as distractions from the search for true wisdom, Aristotle took a more pragmatic view.

He analyzed political systems based on real-world observations, not just abstract reasoning. And he saw the physical world as a source of knowledge, not an illusion to be transcended.

So while Plato’s philosophy pointed towards a utopian idealism, Aristotle planted the seeds of empiricism and the scientific method. The student had indeed diverged from the teacher, and Western thought would never be the same.

Aristotle’s Conception of Substance and Form: Aristotle and Plato

At the heart of Aristotle’s break with Plato was his unique understanding of substance and form. For Aristotle, substance wasn’t some abstract, perfect essence in an eternal realm, but a very real thing intrinsic to individual objects. And form wasn’t a universal property, but the specific arrangement of an object’s physical components.

The Distinction Between Primary and Secondary Substances

Aristotle made a key distinction between “primary” and “secondary” substances. Primary substances are individual things – this particular oak tree, that specific horse. They’re the basic building blocks of reality. Secondary substances are the broader categories or species that primary substances belong to – tree, horse, animal.

As The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy notes, for Aristotle “the items in the ontology that are the paradigm subjects of predication are the primary substances, and they are subjects of predication in the fullest sense.”

In other words, when we say “Secretariat is a horse,” the primary substance is the individual horse Secretariat, not the secondary substance or category of “horse.” Aristotle saw primary substances as the fundamental units of being.

Hylomorphism: The Unity of Form and Matter

Another key concept for Aristotle was hylomorphism – the idea that every substance is a compound of both matter and form. The matter is the physical “stuff” a thing is made of, while the form is the way that matter is arranged. You can’t have one without the other.

Aristotle used a bronze statue as an example. The matter is the bronze itself. The form is the shape the sculptor imposes on it. Change the form (melt the statue down) and you change the substance itself, even if the matter remains the same. The form and matter are inextricably linked.

This stood in stark contrast to Plato’s idea of Forms existing independently of physical things. As The Collector puts it, “Things can only be understood as compounds of form and matter. In other words, he thought the forms do not exist independently, which is why he was so critical of Plato’s view that they do.”

For Aristotle, substance and form weren’t abstract, free-floating essences, but concrete properties of actual, individual things. This grounding in the real world of sensory experience would become a hallmark of Aristotelian thought, shaping his contributions to logic, biology, ethics, and beyond.

Key Takeaway: Aristotle and Plato

Aristotle and Plato, once teacher and student, diverged sharply in their philosophies. Aristotle rejected Plato’s abstract Theory of Forms, favoring a more tangible approach that tied forms to physical objects. This split not only marked a significant intellectual rivalry but also laid the groundwork for empiricism over idealism.

Actuality and Potentiality in Aristotle’s Metaphysics: Aristotle and Plato

Aristotle’s metaphysics is a complex and multi-faceted exploration of the fundamental nature of reality. At the heart of his philosophy lies the concept of actuality and potentiality, a distinction that has far-reaching implications for our understanding of change, substance, and the very fabric of existence.

According to Aristotle, everything in the world is a combination of both actuality and potentiality. Actuality refers to the current state of a thing, while potentiality represents its capacity for change or development. In other words, actuality is what a thing is, while potentiality is what it could be.

The relationship between actuality and potentiality is a crucial aspect of Aristotle’s metaphysics. He argues that actuality is prior to potentiality, both in terms of logic and in terms of substance. This means that for something to have the potential to be a certain way, there must already be something actual that embodies that potential.

For example, a block of marble has the potential to become a statue, but this potential can only be realized through the actual work of a sculptor. The sculptor’s actuality (their skill and labor) brings out the potentiality inherent in the marble.

Aristotle also maintains that actuality is prior to potentiality in terms of time. He reasons that for something to be potential, there must have been a prior actuality that gave rise to it. In other words, potentiality is always grounded in and dependent upon actuality.

The Role of Change in Aristotelian Metaphysics: Aristotle and Plato

Change is a fundamental concept in Aristotle’s metaphysics, and it is closely tied to his understanding of actuality and potentiality. For Aristotle, change is the process by which potentiality becomes actuality. It is the transition from one state of being to another.

Aristotle identifies four types of change: substantial change (generation and corruption), quantitative change (increase and decrease), qualitative change (alteration), and change of place (locomotion). Each of these types of change involves the actualization of a potentiality.

“Aristotle’s conception of form and matter finds further expression in that of actuality and potentiality, as found in The Metaphysics. Form is associated with actuality, and matter with potentiality. Potentiality is the ability of something to undergo change and become a certain form, or to attain an actuality.”

– Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, “Aristotle’s Metaphysics“

Ultimately, Aristotle’s understanding of change is teleological, meaning that it is directed towards an end or purpose. He believes that the world is not a chaotic or random place, but rather a rational and ordered system in which things strive to actualize their potential and fulfill their essential nature.

The Influence of Aristotle’s Philosophy: Aristotle and Plato

Aristotle’s philosophy has had a profound and lasting impact on Western thought. He’s tossed big ideas into the mix that have really turned heads, making waves in everything from science and politics to how we figure out right from wrong, and even those deep questions about existence itself.

A big part of what makes Aristotle a superstar in the world of deep thinking is how he gave logic its first major workout. Aristotle is often credited with being the father of formal logic, having developed a system of reasoning that was used for centuries and remains influential to this day.

Aristotle’s Impact on Western Philosophical Tradition: Aristotle and Plato

Aristotle’s impact on Western philosophy cannot be overstated. His ideas have been studied, debated, and built upon by generations of thinkers, from the ancient world to the present day.

In the Middle Ages, Aristotle’s works were rediscovered and translated into Latin, sparking a renewed interest in his philosophy. Medieval thinkers such as Thomas Aquinas sought to reconcile Aristotelian philosophy with Christian theology, leading to the development of Scholasticism.

During the Renaissance, thinkers such as Galileo and Descartes challenged Aristotelian ideas about the natural world, leading to the development of modern science. However, Aristotle’s influence continued to be felt in fields such as ethics, politics, and metaphysics.

In the modern era, Aristotle’s ideas have been both celebrated and critiqued. Some thinkers, such as Ayn Rand, have embraced Aristotle’s emphasis on reason and logic, while others have challenged his views on topics such as slavery and women.

“Aristotle’s philosophy has had a profound impact on the Western philosophical tradition. His ideas about logic, metaphysics, ethics, and politics have shaped the course of intellectual history and continue to be studied and debated to this day.”

– Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, “Aristotle“

The Enduring Relevance of Aristotelian Thought

Despite the many challenges and critiques that Aristotle’s philosophy has faced over the centuries, his ideas remain relevant and influential to this day. His emphasis on reason, logic, and empirical observation has had a lasting impact on Western thought, shaping our understanding of the world and our place in it.

Aristotle’s ideas on ethics, which zoom in on virtues, personal character, and the quest for a fulfilling life, still spark conversations and debates among both thinkers and everyday folks. His political philosophy, with its analysis of different forms of government and its emphasis on the common good, remains relevant to contemporary debates about democracy, justice, and the role of the state.

Aristotle’s ideas still hit home today, and that’s because he really paid attention to the world around him and thought things through logically. His ideas continue to shape our understanding of the world and our place in it, from ethics and politics to science and metaphysics.”

– Shields, C., “Aristotle”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2020 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2020/entries/aristotle/.

Key Takeaway: Aristotle and Plato

Aristotle’s concepts of actuality and potentiality reveal how everything is a blend of what it is now and what it could become, highlighting change as the journey from possibility to reality. This foundation influences our grasp on existence, shaping fields from logic to ethics.

Understanding the Human Condition Through Aristotle and Plato

Plato and Aristotle’s philosophical insights into the human condition remain as relevant today as they were over 2,000 years ago. Their thoughts keep shaping our grasp of what it really means to be a part of the human race.

Plato and Aristotle recognized that humans are complex beings with both rational and irrational impulses. We strive for meaning, purpose, and the “good life” while also grappling with our baser instincts and desires.

Both philosophers sought to understand the fundamental nature of human existence. What drives us? What fulfills us? How can we live virtuously and achieve eudaimonia – the highest human good?

Plato’s Tripartite Theory of the Soul: Aristotle and Plato

Plato took a different approach to understanding human nature and the good life. He developed a tripartite theory of the soul, dividing it into three parts: reason, spirit, and appetite.

For Plato, the rational part of the soul should rule over the spirited and appetitive parts. When reason governs our emotions and desires, we live justly and harmoniously. But when the lower parts overthrow reason, our lives fall into disorder.

Plato used the metaphor of a charioteer (reason) driving two winged horses:

– The white horse of spirit, which represents our higher emotions like courage and righteousness.

– The black horse of appetite, which represents our baser instincts and cravings.

The charioteer’s job is to guide the horses towards enlightenment and the Good. But it’s a constant struggle to rein in the unruly black horse and channel the white horse’s noble passions.

Key Takeaway: Aristotle and Plato

Dive deep into the minds of Aristotle and Plato to see how their timeless insights help us navigate life’s big questions, like what it means to be truly happy or live a good life. They show us that understanding our complex nature and striving for virtue is key.

Conclusion: Aristotle and Plato

The journey through Aristotle and Plato’s philosophies is more than a trip back in time—it’s a mirror reflecting our own quests for knowledge, meaning, and purpose. Their rivalry wasn’t merely academic; it was a clash of visions that continues to challenge our perspectives. As we unpacked their arguments on forms versus substance or potentiality against actuality,

we weren’t just exploring abstract concepts.

We were delving into questions at heart since antiquity:

What constitutes a good life?

How do we understand reality?

In essence,

AristotleandPlato‘srivalry teaches us

that questioning,poking,

and prodding at ideas—no matter how established they may seem—isn’t just an intellectual exercise;i>t’sa vital partf humanity’s never-ending quest for wisdom.

This dance(if you will)beween theory and application reminds us : The search fn the continuous pursuit o.