Ever stopped to wonder what really makes us tick? Aristotle did. Diving into “Aristotle on the soul” wasn’t just an intellectual exercise; it laid down the first bricks for what would become a sprawling road of philosophical thought that’s been traveled for generations. His take is not about some intangible essence but something far more foundational to our existence. Imagine peeling back layers to reveal what makes life, well, alive. That’s where we’re headed.

Aristotle saw the soul as intertwined with our very being – not separate entities battling for dominance but harmonious partners in defining life itself. This perspective challenges us to rethink notions of identity and existence.

Table of Contents:

- Aristotle’s Concept of the Soul

- The Three Parts of the Soul

- The Soul’s Relationship to the Body

- Aristotle’s Influence on Later Thought

- Conclusion

Aristotle’s Concept of the Soul: Aristotle on the Soul

Aristotle’s concept of the soul is a game-changer.

It’s not some spooky ghost trapped in our bodies. Aristotle sees the soul as the “form” that makes a living thing what it is.

The Soul as the Form of the Body: Aristotle on the Soul

For Aristotle, the soul is the essence or “form” of a living body. Just like the form of a statue is what makes it a statue, the soul is what makes a living thing alive.

Aristotle identifies soul with form, and body with matter. He assumes that to have a soul is to have the functional properties that are the form, and the relation of the soul to the body is the relation of the form to matter, and of actuality of potentiality.

Hylomorphism and the Soul-Body Relationship

Aristotle’s hylomorphism is key to understanding his view of the soul-body relationship. Hylomorphism sees things as a combo of matter and form.

The soul is the form. The body is the matter. They’re two sides of the same coin, inseparable.

The Soul as the Cause of Life

For Aristotle, the soul is the source of life itself:

The soul is the mark of a living thing — if it has a soul, then it is alive, and if not, then it is not.

The soul isn’t some separate entity. It’s the very essence and cause of a living being.

The Three Parts of the Soul: Aristotle on the Soul

Aristotle breaks down the soul into three main parts or faculties:

- The Nutritive Soul

- The Sensitive Soul

- The Rational Soul

Each part has its own unique functions and powers.

The nutritive soul is the most basic. It’s what allows living things to grow, reproduce, and sustain themselves. Even plants have this “vegetative soul.”

The Sensitive Soul

The sensitive soul is a step up. It gives animals the power to sense, desire, and move. Dogs, cats, all the creatures with senses have the sensitive soul.

The Rational Soul: Aristotle on the Soul

The rational soul is the cream of the crop. It’s unique to humans and grants us the ability to think and reason. This is what sets us apart from the rest of the animal kingdom.

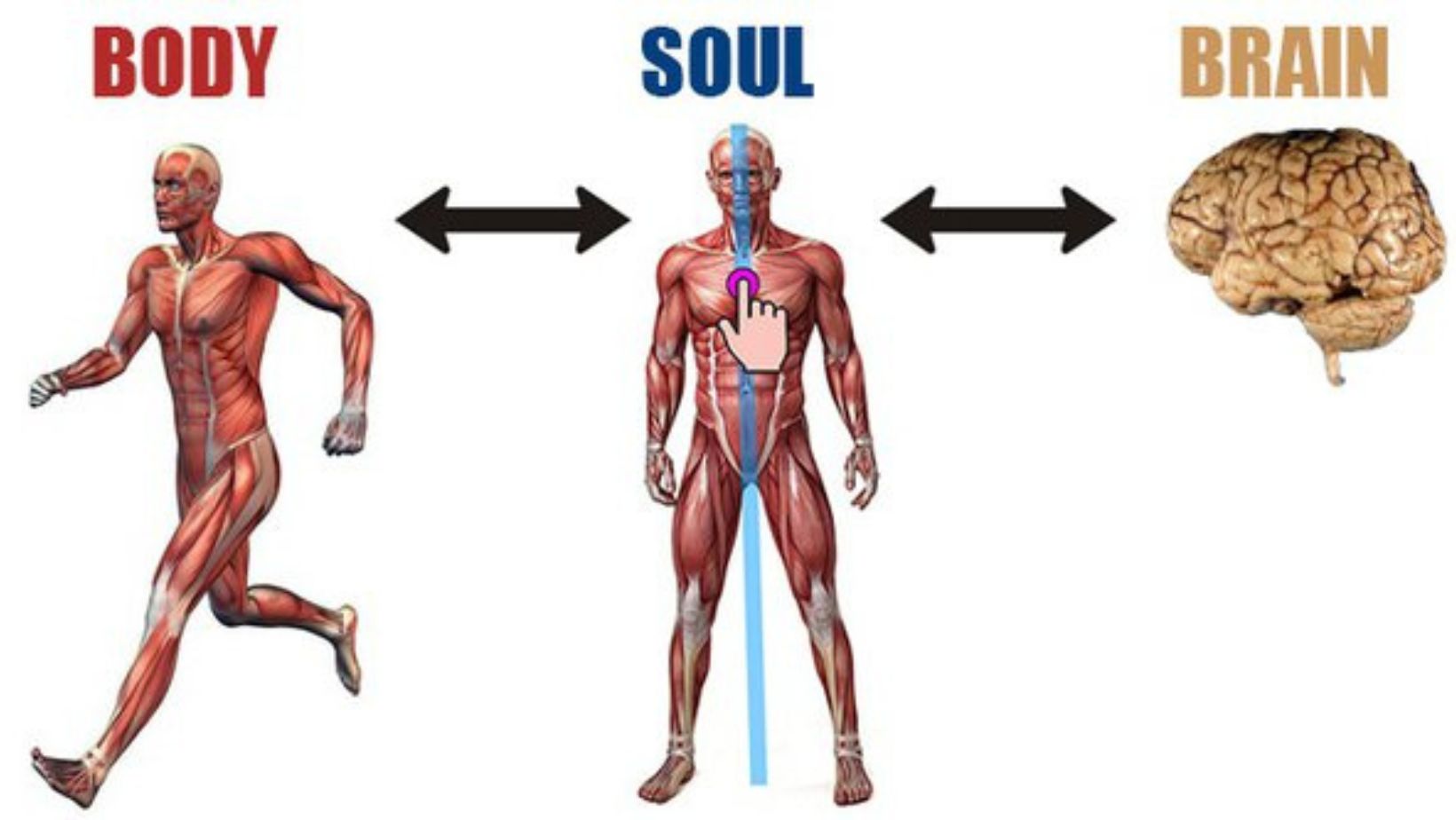

The Soul’s Relationship to the Body: Aristotle on the Soul

So how exactly does the soul relate to the body in Aristotle’s view? Let’s break it down.

The Soul as the Actuality of the Body

Aristotle sees the soul as the “actuality” or fulfillment of the body. The body has the potential for life, and the soul is what actualizes that potential.

Aristotle identifies soul with form, and body with matter. He assumes that to have a soul is to have the functional properties that are the form, and the relation of the soul to the body is the relation of the form to matter, and of actuality of potentiality.

The Inseparability of Soul and Body: Aristotle on the Soul

For Aristotle, you can’t have a soul without a body or a body without a soul. They’re two integral parts of a whole.

Clearly, in Aristotle’s conception of the soul, there is neither a relation of identity nor a relation of complete difference between the body and soul — they are, in effect, different aspects of the same totality.

The Soul as the Cause of the Body’s Functions

Aristotle argues that the soul is the source of all the body’s functions and activities:

Aristotle begins by observing that all forms of behavior, human or animal, require a body. Even supposedly ‘mental’ states, such as anger, love, and desire, all have concomitant physical manifestations: an angry man gets red in the face, a man in love stares at his beloved, and a man who desires alcohol tries to get it.

Aristotle’s Influence on Later Thought: Aristotle on the Soul

Aristotle’s concept of the soul had a massive impact on Western philosophy and beyond. Let’s see how.

The Impact on Medieval Philosophy

Aristotle’s ideas shaped medieval thought in a big way:

Aristotle’s account of the soul is the most extensive and explicit of any Greek philosopher.

Medieval thinkers like Thomas Aquinas drew heavily on Aristotle’s concepts.

The Influence on Christian Theology: Aristotle on the Soul

Aristotle’s view of the soul also influenced Christian theology, although not without some tension:

Here and elsewhere there is detectable in Aristotle, in addition to his standard biological notion of the soul, a residue of a Platonic vision according to which the intellect is a distinct entity separable from the body.

Modern Interpretations of Aristotle’s Theory

Believe it or not, Aristotle’s ancient theory still has relevance today:

This conception is still popular in the philosophy of mind today and indeed appears to capture something about the subtle relationship between our minds and our bodies quite well.

While not without its critics, Aristotle’s view of the soul-body relationship continues to inspire modern debate and discussion.

Key Takeaway: Aristotle on the Soul

Aristotle rocked the boat by defining the soul not as a ghostly presence, but as the essence that makes living things alive. He broke it down into three parts: nutritive for growth, sensitive for perception and movement, and rational exclusively in humans for thought. His big idea? The body and soul are inseparable, challenging how we think about life itself.

Conclusion: Aristotle on the Soul

The journey through Aristotle’s thoughts on the soul leaves us at a crossroads between ancient wisdom and modern interpretation.

We’ve seen how this legendary philosopher took apart concepts like form and matter only to intertwine them again in ways that challenge our understanding of ourselves. Far from portraying AI-like doomsday scenarios or abstract metaphysics, Aristotle gave us a down-to-earth account – one where every living thing holds a unique place in nature’s grand tapestry because of its soul.

In wrapping up, let’s carry forward these insights as tools for introspection rather than mere historical footnotes. Our exploration into “Aristotle on the soul” doesn’t end here; it starts anew with each reflection upon our own lives’ purposeful design.